Aminimum wage increase looms in Malaysia, but a standoff continues over when it should take effect. Workers want the revised level of RM1,500 per month, up from the current RM1,200, to kick in by mid-2022. Employers seek to defer enforcement until year-end.

RM1,500 represents a national milestone figure of sorts. The Malaysian Trades Union Congress has appealed for this amount of minimum wage since 2013; the main contenders of the 2018 general election, Pakatan Harapan and Barisan Nasional, both promised to raise it to, yes, RM1,500. This sum was finally approved in late 2021, likely in the aftermath of deliberations by the tripartite National Wage Consultative Council (NWCC). But on 19th February, Prime Minister Ismail Sabri announced — without committing to a timeline — that his administration will hold further rounds of stakeholder engagement before making a final decision.

Malaysia’s past experiences and present economic circumstances demand attention, but it is also paramount to refocus on the purpose and process of minimum wage. The ongoing engagements, while negotiating contending interests, must not compromise on the moral underpinnings. Minimum wage is, first and foremost, a social instrument for ensuring that full-time workers can meet basic needs.

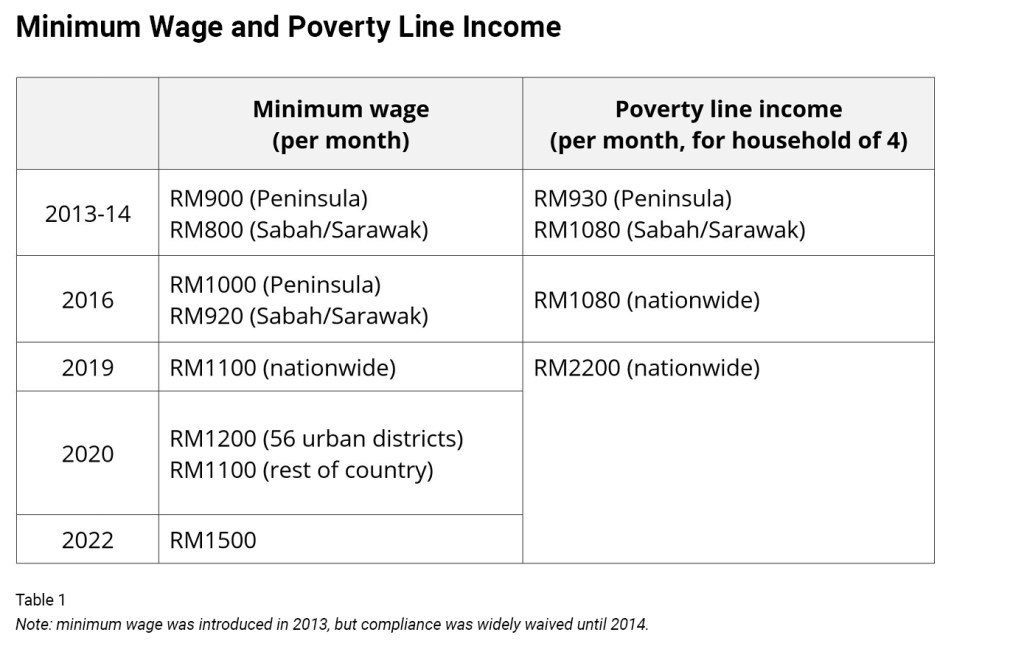

The NWCC’s wage-setting formula has two core elements — basic needs and market wage conditions — with adjustments based on economic indicators. The computation references the poverty line income (PLI) — the income threshold below which a household is considered poor – and median wage earned by the worker. Productivity, inflation and unemployment also factor into the equation. Using this formula, Malaysia introduced minimum wages of RM900 for Peninsular Malaysia and RM800 for Sabah and Sarawak in 2013-14.

Importantly, in 2019, after years of criticism for maintaining an unreasonably low PLI which undercounts poverty, Malaysia reset the PLI. Whether or not the 2019 PLI impacted on the 2022 minimum wage revision to RM1,500 is uncertain, but as shown in Table 1, RM1500 is more aligned with the new PLI of RM2200, buttressing the minimum wage increase and the case for it to be paid soon. The current shocks in energy and food prices, which will undoubtedly raise costs of living further, add to the urgency of lifting the wage floor.

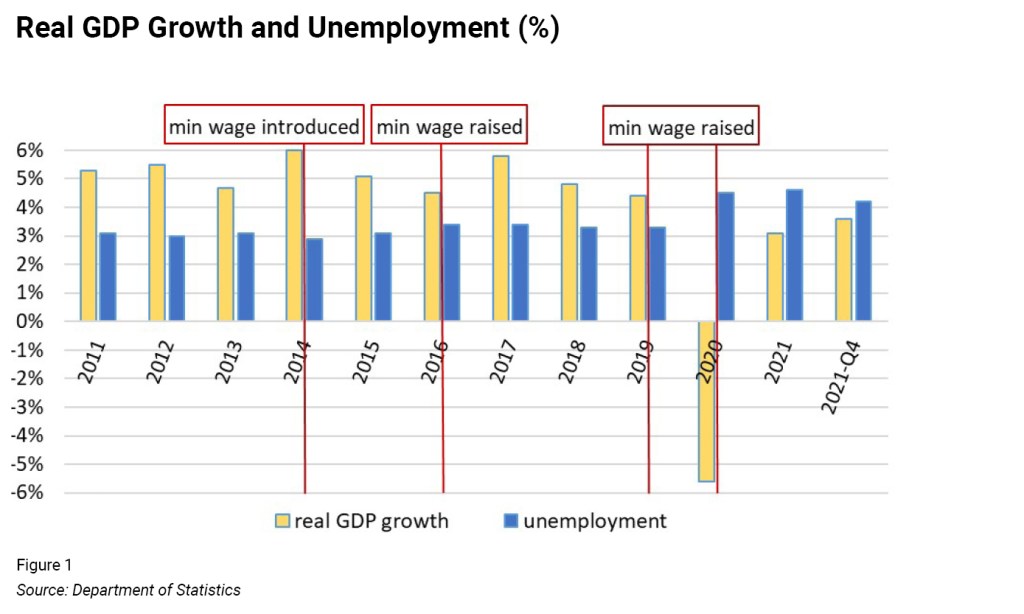

Experience suggests the economy can absorb the rising minimum wage. As shown in Figure 1, the inauguration of nationwide minimum wage in 2014, and increases in the minimum wage level in 2016 and 2019, did not trigger widespread job losses, despite the Malaysian Employers Federation’s (MEF) dire premonitions whenever the minimum wage is being reviewed. Unemployment and GDP growth rates held steady in those years. In 2020, the decision to raise minimum wage preceded the pandemic and the economic recession. Still, the official unemployment rate did not skyrocket.

Of course, the current minimum wage hike, at 25 per cent, is steeper than previous ones. From 2016 to 2019, minimum wage increased by 10 per cent, from RM1,000 to RM1,100, and then rose a further nine per cent to RM1,200 in 2020. Throughout 2014–2019, amid minimum wage introduction and a few increases, unemployment hovered within 2.8–3.4 per cent, then rose to 4.5–4.6 per cent in pandemic-battered 2020 and 2021. Unemployment steadily declined from 4.8 per cent in July 2021 to 4.2 per cent in December 2021. Labour market recovery is underway, but minimum wage rollout may require some nimbleness to address the concerns of slower recovering sectors and small companies.

Workers’ wages have taken a big hit. Median wage fell by 16 per cent in 2020, based on the national Salaries and Wages Survey. Twenty-somethings, who constitute 31 percent of total employees, suffered a larger drop of 18 per cent. The median wage of 20–24-year-olds shrank from RM1,577 in 2019 to RM1,289 in 2020. In other words, half of young employees earn substantially less than RM1,500. The state of young workers, comprising the majority of low-wage earners, is pertinent since they rely more on minimum wage. Wages presumably rebounded in 2021, although survey results for the year have not yet been published. However, the pedestrian economic pace of 2021 indicates that workers have not regained the wages lost in 2020.

More can be done for the transition. The under-utilised Employment Insurance System, established precisely for scenarios such as this, should be invigorated so that it can provide any displaced workers with financial and job-seeking assistance. Short-term measures like sector-based or company size-based deferrals might be negotiated — as a very last resort. The longer-term challenges of increasing labour productivity also warrant continued attention, including the MEF’s appeal for the foreign worker levy collected by government to be channelled toward helping companies mechanize.

The MEF has recently reprised one of its stock answers for resisting minimum wage raises: foreign workers will predominantly benefit, and they will remit most of the increased income to their families abroad. Non-citizens undeniably fill the majority of low-paying jobs, but constraining minimum wage growth because of the nationality of recipients is a regressive stance.

A sizable portion of Malaysian workers earn at or near the minimum, and jobs paying slightly above the legal wage floor may also be induced to pay more when the floor rises. Minimum wage remains a key instrument in the national aspiration to be an advanced economy and inclusive society. The higher purpose must drive the policy.

By Lee Hwok-Aun / fulcrum

The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of AsiaWE Review.