Cambodia’s hearty relations with Russia means that it should have taken a less strident view of the latter’s invasion of Ukraine. Intriguingly, Phnom Penh’s position has tacked closer to Western critics of the Kremlin.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February elicited fairly predictable responses from the ASEAN member states.

Cambodia’s stance, however, has taken many by surprise.

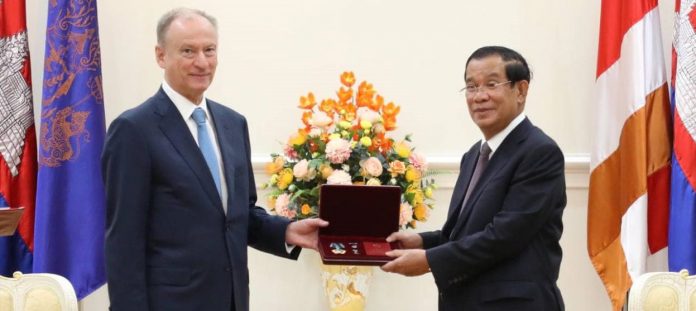

At the outset of the conflict, most observers assumed that Cambodia would adopt a neutral position. After all, Prime Minister Hun Sen’s relations with Russia have been quite cordial, to the extent that the Kremlin awarded him a friendship medal late last year. Moreover, as his anti-democratic tendencies have increased, his comradeship with fellow autocrats such as Russian President Vladimir Putin and Chinese President Xi Jinping has grown.

Hun Sen’s initial response to the invasion seemed to confirm his critics’ worst fears. On the day of the invasion on 24 February, he merely expressed hopes for a ‘peaceful resolution’ of the dispute. A week later, he implied that Cambodia would not take sides.

In fact, Hun Sen appears to have decided early on not to sit on the fence. According to one reliable source who spoke with the author, while the country’s foreign ministry wanted to follow Vietnam and Laos in abstaining from the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) vote that condemned Russia on 2 March, Hun Sen personally ordered his diplomats in New York not only to support it, but to co-sponsor the resolution.

Cambodia’s vote at the UNGA was seemingly at odds with the recent carriage of the country’s foreign policy. The Prime Minister’s view aligned with those of his Western critics, while he admitted ignoring the entreaties of a great power friend (either Russia or China, or the former through the latter) to abstain.

As the conflict unfolded, Hun Sen’s views hardened. Meeting with Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida on 21 March, the two leaders called Russia’s invasion a ‘grave breach’ of the United Nations Charter and that Moscow’s behaviour ‘jeopardises the foundation of international order’. Although they did not name Russia, the statement was stronger than the one issued by Kishida and Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modhi a few days earlier.

By the end of March, Hun Sen was calling the Kremlin’s military operation in Ukraine an ‘act of aggression’ and that Cambodia ‘cannot remain neutral’. He called into question Russia’s ability to defeat Ukraine on the battlefield and even said he was open to taking in Ukrainian refugees.

Two main reasons account for Hun Sen’s hard-line views on the Russia-Ukraine War.

In opposing the invasion, the Prime Minister invoked both principle and history. Cambodia was, he said, against the war because ‘We pursue a foreign policy based on the law and the UN Charter. We do not pursue a foreign policy based on force.’

Although the Russian ambassador was keen to remind Cambodia of Moscow’s help during the Cold War, Hun Sen stated that he was not afraid of angering the Kremlin. He can afford to do so: two-way trade is modest (only US$95 million in 2021) and, unlike Vietnam, Cambodia is not dependent on Russia for military equipment.

Hun Sen also mentioned Cambodia’s past experiences, noting that ‘Cambodia’s independence and sovereignty were once invaded’. He did not name which country had done so, but many observers assumed he was talking about Vietnam’s invasion in 1978. In fact, it was not Vietnam. For Hun Sen, a former Khmer Rouge soldier who had defected to Vietnam in 1977, Hanoi’s occupation of the country was not an invasion but an act of liberation. What Hun Sen was probably alluding to was Thailand’s occupation of land near the Preah Vihear Temple in 2007 and 2008, for which he has never forgiven Bangkok.

Hun Sen is also against Russia’s invasion because of its severe economic consequences. As with other Southeast Asian countries, Cambodia is concerned that rising food and energy prices, together with the war’s impact on the lucrative tourism industry (which accounted for 12 per cent of the country’s GDP in 2019) will hinder its economic recovery from the Covid-19 pandemic. With Chinese tourists forced to stay at home due to Beijing’s ‘zero-Covid’ policy, the rising cost of aviation fuel and the closure of air space over Ukraine and Russia, Cambodia’s tourism resorts may continue to struggle for a lot longer.

Although the Russian ambassador was keen to remind Cambodia of Moscow’s help during the Cold War, Hun Sen stated that he was not afraid of angering the Kremlin. He can afford to do so: two-way trade is modest (only US$95 million in 2021) and, unlike Vietnam, Cambodia is not dependent on Russia for military equipment.

The war could, however, cause problems for Cambodia’s 2022 chairmanship of ASEAN.

Russia is a Dialogue Partner (DP) of ASEAN and participates in the full panoply of ASEAN-led multilateral meetings such as the ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF), the ASEAN Defence Ministers’ Meeting Plus (ADMM-Plus) and the East Asia Summit (EAS).

Cambodia is obliged to invite Russia to all the meetings, but most of ASEAN’s Western DPs and Japan have indicated they may boycott the meetings if Russia attends. Thailand is facing the same problem with APEC and Indonesia with the G-20 Summit.

While this poses a diplomatic headache for the countries concerned, it is probably not an existential threat to multilateralism.

Those DPs which oppose Russia’s invasion will not want to embarrass the summits’ hosts, nor cede the floor to China and Russia in their absence. More likely, they will turn up but cold shoulder the Russian delegations and walk out when they speak — as has already happened at G-20 and APEC ministerial meetings.

As for the EAS, Putin has only attended once in person, and probably will avoid travelling this year for fear of a palace coup while he is abroad. He may appear virtually or send his low-key Prime Minister Mikhail Mishustin. ASEAN’s DPs can probably live with either. So can Hun Sen, even if the Russians ask him to hand back his friendship medal./By IAN STOREY/ FULCRUM