EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

- Japan’s maritime capacity-building assistance for Vietnam, which includes training seminars, joint exercises and equipment transfer, has become a prominent feature in bilateral cooperation.

- The cooperation is driven by their increasingly convergent strategic interests, including preserving the safety of maritime trade routes and countering China’s increasing assertiveness in territorial and maritime disputes. Capacity-building assistance for Vietnam is also in line with Japan’s Free and Open Indo-Pacific vision for an international rules-based order.

- Vietnam is receptive to Japan’s assistance due to the high level of political trust between the two countries and to Hanoi’s wish to mobilize resources for its hedging strategy against China.

- The prospect for bilateral maritime capacity-building cooperation is promising, especially if Japan works with its allies and partners to coordinate their assistance for Vietnam.

INTRODUCTION

Japan has traditionally been a provider of maritime capacity-building assistance for Southeast Asian states, offering activities ranging from joint exercises, training opportunities in Japan for defence personnel to equipment transfer. The assistance aims to strengthen the capacity of these countries in maritime domain awareness and law enforcement, thereby facilitating faster and more effective responses to security challenges.

Among Southeast Asian states, Vietnam has emerged as a prioritized partner for Japan’s maritime capacity-building initiatives. Driven by a confluence of strategic interests, including the safety of maritime trade routes and growing alarm over China’s behaviour in territorial and maritime disputes, Japan and Vietnam have cooperated extensively to enhance the latter’s maritime capacity. Cooperation initiatives include training seminars, joint exercises between navies and coast guard forces, as well as equipment and technology transfers. Vietnam sees Japan as an ideal partner in its quest for military and law enforcement modernization and its struggle against China in the South China Sea. For Japan, capacity-building assistance for Vietnam is in line with its Free and Open Indo-Pacific (FOIP) vision, in which Tokyo seeks to enhance the capacity of Southeast Asian states to promote a regional rules-based order.

JAPAN-VIETNAM STRATEGIC PARTNERSHIP

Japan and Vietnam have been enjoying a solid bilateral partnership covering economic, political and security cooperation. With US$60 billion investments in 4,641 projects as of 2020, Japan is Vietnam’s second-biggest foreign investor.[1] Japan is also a top provider of official development assistance (ODA) to Vietnam, sending the country US$650 million in grants, loans and equity investment in 2019.[2] On the political front, the two countries established an extensive strategic partnership in 2014 and agreed to deepen it three years later. Japan has thus emerged as a close security partner of Vietnam, providing the latter with patrol vessels and maritime security-related equipment.

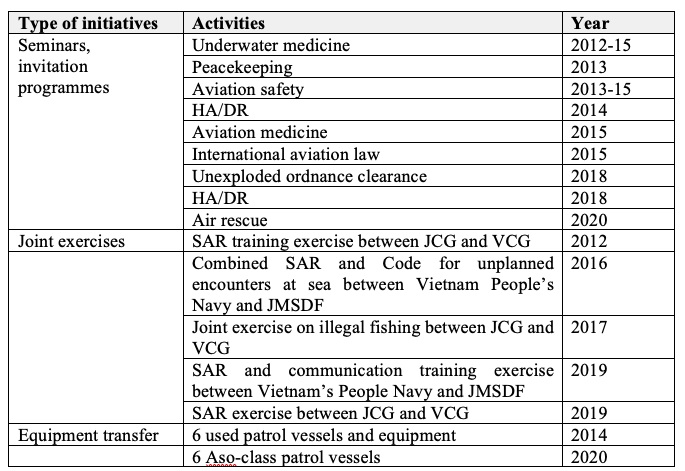

The foundation for capacity-building cooperation between Japan and Vietnam has been laid out in a series of official documents. The two countries kickstarted their security engagement by signing a memorandum of understanding on defence cooperation in 2011, which promised capacity-building initiatives such as defence personnel training in Japan, cooperation in search and rescue (SAR), humanitarian assistance/disaster relief (HA/DR), counterterrorism, military medicine, IT training, and peacekeeping.[3] In the 2014 Joint Statement on the Establishment of the Extensive Strategic Partnership for Peace and Prosperity in Asia, both sides announced their intention to advance cooperation in capacity-building, particularly by enhancing the capacity of Vietnam’s maritime law enforcement agencies.[4] During the visit of Prime Minister Nguyen Xuan Phuc to Japan in 2017, Japan and Vietnam agreed to deepen their strategic partnership and advance capacity-building initiatives, including information exchange between coast guard agencies.[5] In 2018, the two sides signed a Joint Vision Statement on Defence Relations, promising more military exchanges, cooperation in aviation search and rescue and peacekeeping operations.[6] The following table summarizes the main types of capacity-building initiatives that the two countries conducted between 2012 and 2020.

Japan’s Capacity-building Initiatives with Vietnam 2012-20

JAPAN’S STRATEGIC INTERESTS

As a resource-poor country pursuing export-led growth, Japan pays constant attention to maintaining the safe transit of goods along critical sea lines of communication (SLOC). Several of these SLOCs are located in the South China Sea and fall within the jurisdiction of Southeast Asian littoral states such as Indonesia, Malaysia, The Philippines, Singapore and Vietnam.[8] In 2016, 42 per cent of Japan’s maritime trade passed through the South China Sea.[9] However, Japan has been facing several maritime security challenges in this area, which threatens the safety of ship passage with repercussions for Japan’s economic wellbeing. These challenges include traditional and non-traditional threats ranging from natural disasters, maritime safety incidents, illegal fishing, piracy, to territorial and maritime disputes. Southeast Asian littoral states also have varying levels of capacity to respond to these challenges.

China’s growing naval power also complicated Japan’s efforts to protect critical SLOCs. Buoyed by exponential growth over the past 30 years, China has rapidly expanded and strengthened its maritime forces, including its navy and coast guard. The People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) is currently the world’s largest navy with approximately 335 ships as of 2019, while the China Coast Guard (CCG) also ranks as the world’s largest coast guard.[10] China’s assertive posture in territorial and maritime disputes with Southeast Asian claimant states in the South China Sea, and Japan in the East China Sea also presents another grave concern for Japan. Heightened tensions could spiral into open conflicts, potentially disrupting maritime trade flows. Additionally, China’s actions, from its more frequent incursions into waters around the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands and its rejection of the 2016 arbitral ruling to its construction and militarization of seven artificial islands in the Spratlys, pose a challenge to the rules-based international order, which underpins Japan’s prosperity.

Nevertheless, Tokyo faces two major limiting factors in dealing with these challenges. First, Article 9 of Japan’s Constitution states that the country will renounce war as a sovereign right and also the use of force to settle international disputes, thus limiting Japan’s capacity to engage in collective self-defence activities with other countries whose strategic interests are closely aligned with Japan’s.[11] Second, Japan’s imperial legacy from World War II means that it would be more challenging for Japan to openly employ its Self Defence Force (SDF) to conduct maritime security operations in the region,[12] and this action would be deemed controversial by Japan’s anti-militarist society.

Mindful of these constraints, Japan has followed a nuanced and cautious approach in offering maritime capacity-building assistance to regional states, especially to enhance their governance, infrastructure and law enforcement capacity.[13] Starting from the late 1960s, these activities generally focused on maritime accidents, marine environment protection and navigation safety.[14] Tokyo mostly enlisted civilian agencies, notably the Japan Coast Guard (JCG) and the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA), along with private organizations such as the Nippon Foundation, to deliver the assistance.[15] At that time, the nature of Japan’s engagement remained mostly civilian, with restricted roles for its armed forces.

Over the years, new security challenges have emerged, including piracy, terrorism and China’s increasingly assertive postures in territorial and maritime disputes. Japan’s response to the changing environment includes an emphasis on maritime law enforcement, which added a security dimension to its assistance. The expansion of cooperation areas had two main implications: first, an enhanced role for the Japan Maritime Self-Defence Force (JMSDF) as it engaged in more diplomatic and constabulary missions with regional armed forces;[16] and second, Tokyo’s adoption of new legislations to create a legal framework for capacity-building initiatives. Tokyo relaxed its self-imposed arms export ban by introducing the “Three Principles on Transfer of Defence Equipment and Technology” in 2014, allowing arms transfers that contribute to the active promotion of peace and Japan’s security.[17] Later, it revised the Development Cooperation Charter in 2015 to allow for the provision of aid for foreign militaries.[18] These developments were consistent with Japan’s 2012 National Security Strategy, which proposed to accelerate security-related assistance through capacity-building initiatives and strategic utilization of ODA.[19] Japan’s FOIP vision later elevated capacity-building assistance as a core instrument for promoting peace and stability.[20]

While Japan also provides some other Southeast Asian states with maritime capacity-building assistance, its cooperation with Vietnam has grown rapidly and extensively since 2012. An important underlying reason is that Japan sees a connection between its own dispute with China over the Senkaku Islands and the South China Sea disputes. If China is able to coerce other claimants in the South China Sea to accept its claims, this could further embolden China in its confrontation with Japan in the East China Sea. Vietnam, generally considered as the most willing and capable among South China Sea claimant states to stand up to China’s coercion, is therefore a natural maritime security partner for Japan.

Furthermore, a more capable Vietnam in the maritime domain contributes to Japan’s broader strategic goal of preserving the international rules-based order. Tokyo aims to achieve this overarching goal of its FOIP vision through different measures, in which promoting the rule of law and freedom of navigation is key. Stronger maritime capacity will enable Vietnam to better resist coercive actions by China which contravene the international legal norms and undermine the international rules-based order. Moreover, a stronger Vietnam capable of challenging China in the South China Sea can also help lower China’s pressures on Japan in the East China Sea, where Japan has been facing more frequent Chinese intrusions in recent years.

VIETNAM’S RECEPTION OF JAPANESE ASSISTANCE

Vietnam is increasingly receptive to Japan’s overtures in maritime security cooperation because it shares similar strategic interests with the latter, particularly in protecting commercial sea routes and countering China’s increasing assertiveness in the South China Sea. Vietnam’s economic modernization has led the country to become increasingly reliant on foreign trade, and thus on the safety and openness of maritime trade routes in the South China Sea for its economic wellbeing. The importance of these shipping routes will only increase in the future, given Vietnam’s aspiration to become a regional manufacturing and logistics hub. Furthermore, the rise of non-traditional security challenges in the maritime domain, including piracy, illegal fishing, smuggling, natural disasters and climate change, means that Vietnam will need to devote greater resources and attention to maritime security issues.[21] The Vietnam Coast Guard (VCG) recently received some major investments, including six Aso-class patrol boats funded by Japan’s ODA, but still needs more investments for monitoring Vietnam’s vast maritime domain.

Vietnam’s oil and gas activities in the South China Sea have also been disrupted by China on multiple occasions. For example, a major crisis broke out when China moved a giant oil rig into Vietnam’s exclusive economic zone in May 2014, leading to a two-month violent standoff.[22] Tensions rose again in 2019 when the Chinese survey ship Haiyang Dizhi 8 entered waters near Vanguard Bank on Vietnam’s continental shelf and conducted oil and gas surveys across a wide area for four months.[23] In 2020, a CCG vessel reportedly rammed and sunk a Vietnamese fishing boat near the Paracel Islands.[24] China’s construction and militarization of seven artificial islands in the Spratlys also pose a substantial threat to Vietnam’s security.

Against this backdrop, Vietnam highly appreciates Japan’s maritime capacity-building assistance. Despite significant investments in its naval and maritime law enforcement capabilities, Vietnam cannot possibly match China’s military power, leaving the country in a precarious position vis-à-vis China’s incursions.[25] Moreover, there are domains where Vietnam still lacks capabilities, such as the monitoring of its vast maritime domain. This capability is also critical for Vietnam’s efforts to handle natural disasters, deter maritime crimes and enforce its claims in disputed areas. Japan’s assistance, such as the transfer of maritime security-related equipment, therefore strengthens Vietnam’s capability in this regard. In July 2020, a loan agreement was signed for Japan to build six patrol boats for VCG using Japan’s ODA.[26] In September 2021, the two countries signed another agreement to facilitate Japan’s transfer of defence gear and technology, possibly including patrol planes and radars, to Vietnam.[27]

Cooperation with Japan also contributes to Vietnam’s hedging strategy against China. Specifically, Vietnam looks to strengthen security and defence ties with the major powers through a series of comprehensive and strategic partnerships to push back against China’s bullying behaviours. Japan is therefore a priority partner of Vietnam, given the high level of political trust between the two countries. There is no historical baggage in bilateral relations and Tokyo has been consistently supporting Vietnam’s economic development since the early 1990s through both ODA and foreign direct investments (FDI). Through these avenues, Japan has helped Vietnam develop its infrastructure, governance capacity and human resource, which are critical to Vietnam’s economic modernization.[28] Maritime capacity-building cooperation can help further strengthen the overall ties and deepen the strategic partnership between the two countries.

PROSPECTS FOR FUTURE COOPERATION

Japan’s capacity-building assistance for Vietnam is expected to continue as the confluence of strategic interests between the two countries will likely persist. In 2019 and 2020, China dramatically stepped up its incursions into waters around the Senkaku Islands—1,097 times in 2019 and 1,161 times in 2020. Some of its ships also stayed in the area for 333 days in 2020.[29] In the South China Sea, China continued its foray into the exclusive economic zones of Vietnam, The Philippines, Indonesia and Malaysia, harassing their oil and gas exploration activities. China recently passed a controversial coast guard law that grants the CCG sweeping authority, including the right to take “necessary measures” against foreign vessels deemed violating waters under its jurisdiction, including deportation, forced towing, and even “the use of weapons”.[30] This could put patrol vessels of both VCG and JCG under direct threat, further encouraging them to strengthen pragmatic cooperation and policy coordination.

However, Japan’s need to focus on other strategic areas might hamstring its efforts to deepen capacity-building cooperation with Vietnam. Other than surging incursions by CCG vessels into waters around the Senkaku Islands, Tokyo has also been facing increased activities from PLA Navy and Air Force. In fiscal year 2018, Japan Air Self Defence Force (JASDF) had to scramble its fighter jets 675 times to intercept Chinese military aircraft.[3`1] Recently, a group of ten military vessels from China and Russia sailed through the Tsugaru Strait.[32] In response, Japan has since 2012 significantly enhanced its defence posture in its Southwestern region, which covers the Senkaku Islands. Tokyo also needs to keep an eye on the simmering tensions in the Taiwan Strait. Given the proximity between Taiwan and Japan, a Chinese military takeover of Taiwan will risk spreading turmoil to Japan’s Southwestern region and threaten Japan’s main islands.[33] Preparing to respond to these contingencies will require immense resources. Given Tokyo’s high debt level, which rose to a record 1.4 quadrillion yen (US$10.5 trillion) in fiscal year 2020, Japan’s budget for maritime capacity-building programmes will come under great stress.[34] Furthermore, Tokyo also has to prioritize domestic demands, especially post-pandemic economic stimulus packages and social welfare spending to deal with its ageing population.

Vietnam will continue to seek assistance from Japan to strengthen its maritime domain awareness and maritime law enforcement capacity. Japan can meet this demand from Vietnam (and other Southeast Asian states) by coordinating its capacity-building assistance with its key allies and partners, especially the United States, Australia and India, all of which are providing varying levels of capacity-building assistance for Vietnam through bilateral channels; for example, American and Australian experts participated in Japan-led underwater medicine seminars for Vietnam held in 2013 and 2015.

These countries can work together on other joint initiatives to create synergy between their capacity-building programmes. Such collaboration will allow Japan and its allies and partners to share the financial costs, take advantage of each other’s strengths, and optimize their assistance to best meet the maritime capacity-building needs of Vietnam as well as regional countries.

By Hanh Nguyen / iseas

The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of AsiaWEReview.