Emotions underlying voter decision might explain Philippine voters’ overwhelming support for Ferdinand Marcos Jr. as the leading candidate for president of the country, even when the historical record of his family’s notoriety suggests otherwise.

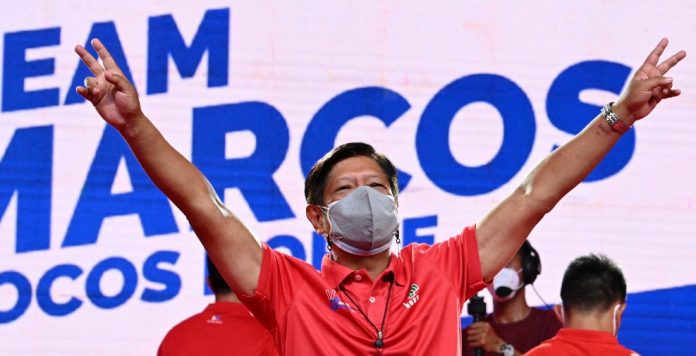

Ferdinand ‘Bongbong’ Marcos Jr. remains the most favoured candidate for the May 2022 presidential elections in the Philippines. Marcos Jr. garnered a 60% public support rating in the latest Pulse Asia survey. This puts him significantly ahead of his closest rival, incumbent vice president Leni Robredo, who slid from 16% to just 15%. For the fiercest critics of Marcos and his notorious family, none of this makes sense. How can the son and namesake of a dictator Filipinos ousted in 1986 for economic mismanagement and human rights violations remain hugely popular? What explains the Marcos family’s enduring appeal to millions of Filipinos, especially among those who lived under the late Marcos’s kleptocratic ‘conjugal dictatorship’?

Understanding how people’s ‘emotional beliefs’ influence their voting preferences may explain this paradox. Jonathan Mercer defines an emotional belief as ‘one where emotion constitutes and strengthens a belief and which makes possible a generalisation about an actor that involves certainty beyond evidence’. I recently expanded on this argument in an article, saying that people experience emotions even without being consciously aware of them. These emotions help people give value to facts when evaluating something as being good or bad. Their decision to accept or reject narratives and political candidates is determined by such emotions.

Drawing on these arguments, we can argue that Marcos Jr.’s promise to ‘bring…unifying leadership back to our country’ to the Filipino voters seems credible if the Filipino voters believe that he will fulfil it. Meanwhile, Robredo’s promise to provide an ‘inclusive government’ of, by, and for the people appears unreliable, if Filipino voters believe that she will not honour her words. This paradoxical situation enables Marcos supporters to neutralise the hostile narratives thrown at their candidate. Accusations that Marcos Jr. is corrupt, a pathological liar, or a morally bankrupt individual are instead projected onto Robredo, whom they see as ‘stupid’, a ‘hypocrite’, and ‘fake’, or even someone who has ‘difficulty speaking in straight English.’ The competing emotions underpinning the Filipino voters’ feelings and experiences vis-à-vis these threats are integral to how they view and perceive the two rival candidates, and how they ultimately vote. The voters’ emotions – ‘of trust or distrust, like or dislike, approval or disapproval, love or hate, pride or humiliation – can be so overpowering that they can convince them of a candidate’s credibility and trustworthiness, even when past records might suggest otherwise.

There are three ways in which emotions influence the Filipino voters’ behaviours and preferences. First, emotions guide voters in selecting and interpreting the body of evidence suggesting Marcos Jr.’s supposed ‘trustworthiness’ and ‘credibility’, and Robredo’s perceived ‘dishonesty’ and ‘unreliability’. Second, these emotions simultaneously engender and strengthen voters’ beliefs concerning the two candidates. Finally, the voters’ emotions towards Marcos and Robredo determine what they believe or believe to be true about these candidates. A quick content analysis of comments posted by the supporters and detractors of both candidates on their respective social media accounts (including on YouTube, Facebook, Twitter, and Tiktok) will show how voter emotions affect politics and fuel political polarisation. As other research shows, a politician’s ‘digital fanbase’ can, in part, be ‘ a reflection of offline, grassroots political support.’

Philippine watchers need to confront and take voters’ emotions more seriously if we want to explain why Filipinos vote the way they do.

It is crucial to point out here that the voters’ ‘pro-Marcos’ or ‘pro-Robredo’ beliefs may change when they are presented with credible evidence. But reversing these beliefs is often difficult, since what voters will eventually accept as convincing explanations will be significantly determined by their prior beliefs. Even though voters have the capacity to change their beliefs based on subsequent evidence, they routinely pick and choose evidence that will fit and support their own beliefs (confirmation bias, in other words).

Emotions are some of the most powerful engines driving voters’ decisions, leading many Filipinos to defiantly support Marcos Jr., while some push for the ‘radical love’ narrative offered by Robredo. The impudence of the Marcos supporters in defending and remaining loyal to the candidate and his family underscores how clashing emotions and emotional beliefs guide the selection, interpretation, and assessment of evidence by Filipino voters on the Marcos family’s history.

Instead of discounting emotions as the opposite of rationality, Philippine watchers need to confront and take these emotions more seriously if we want to more accurately explain why Filipino voters vote the way they do. Removing emotions from the equation prevents us from fully understanding how voters decide who seems to be the most credible and trustworthy presidential candidate. Discounting these invisible albeit powerful emotions creates an inaccurate picture of ‘politics without passion’. As voting is an emotional act, cooler heads need to respect voter sentiment to properly understand Filipino politics. By MICHAEL MAGCAMIT/ FULCRUM