Indonesia President Joko Widodo’s visit to Ukraine and Russia was quite remarkable. But the trip achieved little in finding a way out of the current impasse between Kyiv and Moscow.

For a leader who has often been criticised for showing scant interest in foreign affairs, Indonesian President Joko ‘Jokowi’ Widodo’s visit to Europe in late June was in some ways quite remarkable.

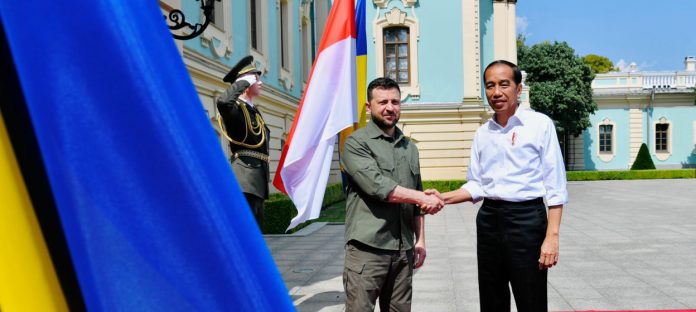

Jokowi became the first Asian leader to meet with both Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy and Russian President Vladimir Putin since the Kremlin launched its invasion of its southern neighbour on 24 February. It was the most high-profile international visit undertaken by an Indonesian leader since President Sukarno undertook a series of visits to Europe, America, China and the Soviet Union in 1956.

So what motivated Jokowi to make the trip and what did he achieve?

Domestic considerations played a key role. Since Jokowi took office in 2014, he has been focused like a laser beam on growing the economy. But economic growth took a hit during the pandemic and the conflict in Ukraine threatens to slow the country’s economic recovery. Rising food and energy prices have fuelled inflation and driven up the price of staples such as cooking oil and instant noodles.

Prior to his trip, Jokowi called for an end to the war and for global food supply chains to be “reactivated”. By travelling to Ukraine and Russia, Jokowi could demonstrate to his people back home that he was trying to alleviate the country’s food crisis at its source.

By meeting with Zelenskyy and Putin he could also show Indonesia’s hallowed “active and independent” foreign policy in action. Since the beginning of the war, Indonesia has tried to maintain a balanced position. It voted to condemn Russia at the United Nations, but has refused to impose sanctions on Russia or send military equipment to Ukraine (though it has provided humanitarian aid). He neither wants to be seen as pro-US or anti-Russian, as neither would sit well with the majority of Indonesians who are generally well-disposed towards Russia and still remember with distaste America’s military interventions in Afghanistan and Iraq.

The President also undertook the trip to try and ensure that the war does not derail the G20 Summit in November. This year Indonesia holds the rotating presidency of the G20 and Jokowi views the Bali summit as the capstone of his two-term presidency, as well as an opportunity to indulge in his favourite passion, encouraging foreign investors to fund the country’s infrastructure needs.

To be fair, the chances that Jokowi’s visit would result in a breakthrough in the conflict were always vanishingly small. Outside of Southeast Asia, Indonesia has little influence in other parts of the world, even the Middle East but especially Europe.

Jokowi has rejected calls by some Western leaders to disinvite Putin from the summit or even expel Russia from the G20 altogether. Instead, and in keeping with his balanced approach to the conflict, he invited Putin as a member of the G20 and Zelenskyy as a guest of the host. Although the threats by Western leaders to boycott the summit have now faded, Jokowi still wants to ensure that the war does not rain on his parade.

Predictably, however, the outcomes of his trip were disappointing.

As a guest of the G7 in Germany, Jokowi urged the grouping to broker peace in Ukraine and resolve the global food and energy crisis but without neglecting the existential threat posed by climate change. While their final communique did prioritise tackling global warming, the G7 leaders also agreed to further tighten sanctions against Russia and send more military aid to Ukraine. A few days later, six of the leaders attended a NATO summit which identified Russia as the alliance’s primary threat and pledged to strengthen the member states’ military forces to deter the Kremlin from further territorial adventurism.

In Kyiv, Jokowi saw the devastating consequences of Russia’s aggression when he visited bombed-out apartment buildings and a hospital. He discussed the food crisis with Zelenskyy, urged him to open dialogue with Putin and reiterated his invitation to the G20 summit. In response, the Ukrainian leader repeated that his physical presence in Bali would depend on how the war develops. If it continues at its current intensity, his participation will likely be virtual.

In Moscow, Jokowi said he had delivered a message from Zelenskyy to Putin, though the nature of that message was not disclosed. When he raised the issue of ensuring grain exports from Ukraine and fertilisers from Russia, Putin blamed the former on the Ukrainians for mining the approaches to their ports and the latter on Western sanctions. He declined to confirm his physical attendance at the Bali summit.

Putin seemed much more eager to discuss strengthening bilateral economic cooperation, including a free trade agreement with the Russian-led Eurasian Economic Union, and supplying Indonesia with nuclear power plants and railways for the proposed new capital in Kalimantan. As the two leaders talked, Russia intensified its shelling of Ukrainian cities.

To be fair, the chances that Jokowi’s visit would result in a breakthrough in the conflict were always vanishingly small. Outside of Southeast Asia, Indonesia has little influence in other parts of the world, even the Middle East but especially Europe.

Moreover, it’s doubtful that Jokowi presented Zelenskyy and Putin with a detailed, well-considered and realistic peace plan. It is equally doubtful that there will be any follow-through to his “peace mission”, either by his foreign minister or former high-profile Indonesian diplomats. His mission was probably a one-off.

At the end of the day, however, Jokowi cannot be faulted for his noble efforts to push for an end to the conflict and an easing of the food crisis which is affecting billions of people.

His heartfelt call for world leaders to “rediscover the spirit of multilateralism, the spirit of peace and cooperation” will be tested in November. It was probably made in hope rather than expectation. BY IAN STOREY/ FULCRUM