Two decades of growth reversed in Southeast Asia’s biggest economy

Things were looking good back in January for Suryanti, an employee at a small travel agent in Bogor, a city south of the Indonesian capital of Jakarta. She had just paid off her motorcycle loan and was planning a vacation with her parents with a bonus she expected to receive from her employer.

And then the coronavirus pandemic hit.

Suryanti was furloughed, the bonus was canceled and she wasn’t paid at all for seven months. The 28-year-old became an online reseller of items such as masks and hand sanitizer, but earned no more than 200,000 rupiah ($14) a week on average.

“The saddest thing was having to sell my motorbike. And because the buyer knew I needed money, they asked for a low price,” Suryanti told Nikkei Asia.

Her company finally asked if she could start working again in September, but both her work hours and pay were cut in half. “I do need the job, though, while many of my friends were either laid off or are still being furloughed — so I just [took the offer],” she said.

Suryanti’s story echoes those of millions of other Indonesians who have lost income or jobs as the coronavirus continues to ravage Southeast Asia’s largest economy. The ripple effects are reversing two decades of steady economic growth marked by declining poverty rates and the rise of a middle class that drove tourism and a tech startup boom.

Furthermore, COVID-19 is causing considerable delays in plans to overhaul Indonesia’s education system as well as major infrastructure projects including the $33 billion relocation of the capital from Jakarta to the island of Borneo. It is making the country’s push to escape the middle-income trap — the phenomenon of previously fast growing economies stagnating at middle-income levels and failing to join the ranks of high-income countries — and become one of the world’s top five economies by 2045 even more herculean.

The Central Statistics Agency, or BPS, said the pandemic had pushed 2.67 million Indonesians into unemployment as of August, inflating the jobless rate to 7.07% — or 9.77 million people. That is a spike from 5.23% a year earlier and the first time Indonesia’s jobless rate has exceeded 7% since 2011.

Over 24 million people became part-timers with reduced work hours and pay and many were pushed into the informal sector. BPS says informal economy workers rose to 60.5% of Indonesia’s total 138 million workforce in August, from 55.9% the year before. That marks a setback to the government’s two decades of efforts to bring more people and businesses back to the formal economy following widespread layoffs during the Asian financial crisis in the late 1990s. Such efforts are important for Indonesia to boost its tax revenue to finance developments, with its tax-to-GDP ratio being one of the lowest in the region.

Subsequently, the average monthly salary dropped 5.18% to 2.76 million rupiah in August from the same month last year. That contributed to weak household consumption, which makes up more than half of Indonesia’s gross domestic product. The economy shrank 3.49% in the July-September period on year, following a steeper 5.32% decline in the previous quarter, sinking Indonesia into its first recession since 1998.

The pandemic is hitting low-income households the hardest, where breadwinners typically have little job security or do informal work that denies them basic protection.

Bogi, a Jakarta taxi driver in his 40s, says he was already hauling fewer passengers before the pandemic due to fierce competition with ride-hailing services. He still struggles to get several passengers a day, despite the city of 10 million people easing movement restrictions in mid-October.

“Sometimes I only bring home 20,000 [rupiah] a day. Sometimes my son and I have to share a cup of instant noodles, or I let him have it all,” says a tearful Bogi. “My son now occasionally goes busking on the street to help his mother and me. My wife jokes that even he earns more than me.”

There are also the so-called sandwich generation families — adults who enjoy better education than their mothers and fathers but have to support both their children and aging parents. The pandemic is stretching them even thinner.

Sri Kurniasih, 31, and her husband are one such family.

Kurniasih stays at home to take care of her three small kids, while her husband is employed at a shipping company in north Jakarta. He has been working full time, six days a week, during the pandemic — but his salary has been cut to 2 million rupiah a month since March, just a third of what it was before the global health crisis emerged.

“That’s not enough because half of the amount is already used to pay the house rent and to send to my husband’s parents in the village,” Kurniasih says, adding she was behind on rent for two months. Like Suryati, she also started selling items online, but earns no more than 500,000 rupiah a month.

Reflecting Indonesia’s steady growth, the poverty rate had been gradually declining from 23% in 1999 to reach 9.66% in 2018 — the first time in the country’s history that it reported a single-digit figure. In July, the World Bank upgraded Indonesia to an upper-middle income economy after more than two decades in the lower-middle income group. The assessment was based on Indonesia’s gross national income per capita having reached $4,050 last year.

But the bleak situation afflicting millions of households suggests that Indonesia could easily fall back into the latter group. The World Bank in October said extreme poverty in the country — based on a $1.9 per day criteria — is projected to increase for the first time since 2006 to 3% this year, rising from 2.7% last year. Poverty rates using higher benchmarks are similarly expected to pick up.

The government has announced a total of 695 trillion rupiah in stimulus packages, or 4.2% of GDP, including 203.9 trillion rupiah for relief aid targeting poor households. But disbursements have been painfully slow due to data discrepancies and bureaucratic inefficiency.

Moody’s warns that the pandemic will exacerbate income inequality, particularly in countries like China, India and Indonesia. Their growth rates have outpaced the rest of the world since 2000, but they also have reported the largest Gini coefficient increases — an indication of growing inequality — among Asia-Pacific nations.

“The pandemic will make inequality starker. Typically, job losses and income shocks disproportionately hurt vulnerable and lower-income groups,” the credit agency says. “Governments with constrained fiscal capacity have limited scope to address the resulting social and political strains, which could amplify credit risks.”

Over the short term, Indonesia is faring better than some of its neighbors. The Asian Development Bank in December forecast the country’s economy would shrink 2.2% this year, a downgrade from a 1% contraction projected in September. That compares with contractions in Malaysia of 6%, the Philippines of 8.5% and Thailand of 7.8%.

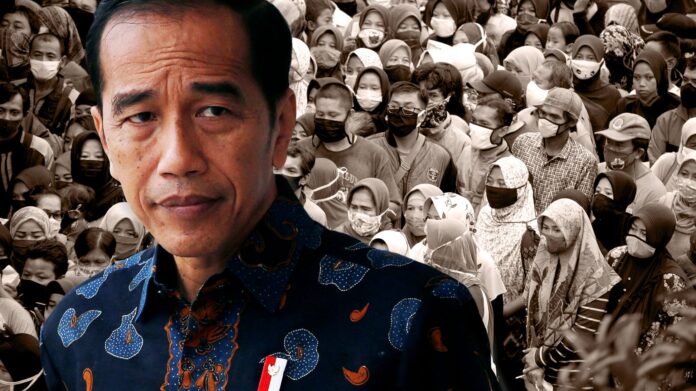

But longer-term repercussions might be worse, as the pandemic is delaying much-needed reforms in education that President Joko Widodo pledged at the beginning of his second, and final, five-year term. After much focus on an infrastructure push in his first term, the president said it was now time to build a skilled workforce that will man his vision for the future, Indonesia 4.0.

“We have a huge potential to escape the middle-income trap,” Widodo said in his inaugural speech after reelection in October last year. “We’re currently at the peak of our demographic bonus. This will pose a big problem if we can’t provide jobs, but will be a big opportunity if we can build superior human resources.”

ADB Country Director for Indonesia Winfried Wicklein said that human resources development — through better education, health and social protection systems — is needed for the country to reach a higher income level. He added that sustainable and quality infrastructure, better access to funding, and higher government revenues are also important factors.

However, Indonesia scores poorly in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development’s Program for International Student Assessment, with about 70% of students scored below the minimum proficiency level for reading in 2018. Meanwhile, the World Bank’s Human Capital Index shows 12.3 years of schooling in Indonesia equates to just 7.9 years of learning. Such factors explain the low productivity and skills that investors complain about.

Instead of reforms, the pandemic and mobility restrictions have kept more than 68 million young Indonesians out of the classroom since March in a blow to learning. The World Bank in a November report said the learning loss during its initial scenario of four-month school closure increased the portion of students failing to meet the minimum reading proficiency to 75% from 70%.

Indonesia’s fiscal deficit is projected to widen to 6.3% of GDP this year to finance stimulus packages and reflect falling tax revenues. The government has won parliamentary approval to remove the deficit ceiling of 3% through 2022, but the country’s debt-to-GDP ratio is projected to expand to 42% of the total economy in 2022 — versus 30% last year.

“It’s a big increase. On the other hand, it’s still very low compared to many other countries,” Ralph van Doorn, acting lead economist at the World Bank office in Jakarta, said in October. “But it’s important to realize if you have more debts, you’ll have to pay more interest payments. So the competition within the budgets for priority spending is going to increase.”

That competition threatens important infrastructure projects essential to reduce logistics bottlenecks and boost export competitiveness, as well as those intended to spur new sources of growth in less developed regions — including the plan to capital move that has been put on indefinite hold.

Finance Minister Sri Mulyani Indrawati on Nov. 5 said that despite the recession “the worst is over,” noting that quarter on quarter, the economy grew 5.05% in July-September. “On the production side, the turning point for economic recovery was seen in the third quarter, which gives us all a big hope — nearly all sectors improved.”

And on Dec. 6, in a sign of hope, the first batch of coronavirus vaccines — 1.2 million doses — from Chinese biopharmaceutical company Sinovac arrived in Jakarta. But there remains uncertainty over the vaccine’s efficacy as well as its procurement and distribution for the entire population of 270 million.

Coronavirus infections, meanwhile, continue to climb nationwide, with cases hitting new highs over the past two weeks — averaging around 6,000 daily. As of Dec. 14, Indonesia had reported a total of 623,309 cases with 18,956 deaths, the highest in Asia after India. Poor testing capacity suggests there could be a lot more cases that have gone undetected, which could lead to a collapse in the limited health care system.

One silver lining is Indonesia’s expanding digital economy that is projected to grow 11% to $44 billion in gross merchandise value this year, outperforming Southeast Asia’s average of 5% — according to the e-Conomy SEA 2020 report by Google, Temasek and Bain & Company released in November. E-commerce is leading the pack with a projected 54% jump to $32 billion. Indonesia’s internet economy is projected to further expand to $124 billion in 2025.

“COVID would be a throwback for sure, but [it is] one more reason for Indonesia to take this opportunity [to accelerate] tech reforms … [and] to have a labor intensive growth, to have green growth and recover as fast as possible and emerge stronger,” Wicklein said.

And an omnibus law, despite its controversy and continued rejection by labor unions, also offers some optimism. Passed in October, the legislation bypasses revisions to as many as 79 laws with the basic aim to simplify bureaucratic procedures and draw more investment.

“The omnibus law passage is quite timely, given the migration of various multinational companies diversifying their supply chains from China. We’ve heard from several corporations that the omnibus law improves Indonesia’s standing compared to Vietnam,” Helmi Arman, chief economist at Citi Indonesia, told reporters last month.

“The omnibus law gives a strong signal for future outlook of reforms in business environment and climate. It can help Indonesia escape the middle income trap,” Arman said./NIKKEI Asia