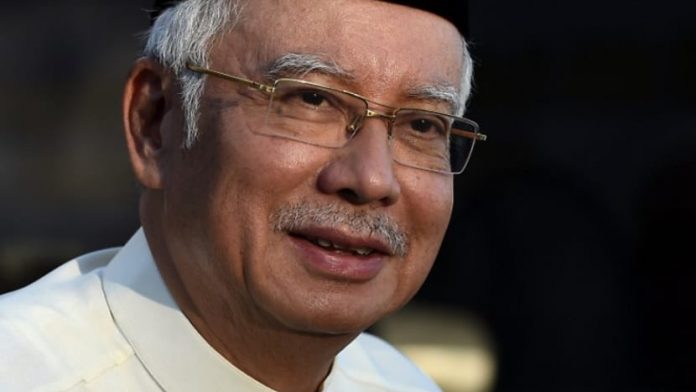

It’s been years since former prime minister Najib Razak was slapped with a swathe of corruption charges and just days since the Court of Appeal upheld his guilty verdict of seven charges in one of the 1MDB cases.

While the news drew a broad range of reactions, some bewailed his conviction in spite of the “overwhelming evidence” against him as set forth by lead judge Abdul Karim Abdul Jalil.

It seems incredulous Najib still has a devout following – what explains his popularity?

GAINING SUPPORT THROUGH ‘SOLVING PROBLEMS’

Many Malaysians believe his fanbase hinges on his ability to scatter reimbursement or “petrol money” in return for supporters to be present at court hearing, campaign events and rallies.

But there are others who willingly support him even without immediate financial compensation.

Political support from Malaysia’s bottom 40 per cent (B40) depends on personal engagement, interaction and proven past assistance.

On home ground, Najib’s electorate, who voted for him overwhelmingly in the last 14th general election (GE14), strongly believe in his ability to serve.

Najib’s constituents in Pekan believe it was his hand that directed investments and development to their town. They now have a highway link to Kuantan, new schools and a university, as well as waterfront development and jobs in the Perak Automotive Park.

His ability to ensure Pekan’s progress endears him to the local populace, nurturing their loyalty.

SELECTIVE MEMORY, LONGSTANDING LOYALTIES

Najib also enjoys the goodwill from the legacy of his late father and Malaysia’s second prime minister, Abdul Razak Hussein.

Abdul Razak launched Malaysia’s oil palm cooperative communities (FELDA) which helped rural Malays become landowners and climb out of abject poverty.

The boom of the palm oil industry and the widespread conversion of arable land from rubber plantations to palm oil fields allowed an entire generation of rural Malaysians to provide for their families.

Today, many FELDA settlers, especially the older generation in east Johor, feel indebted to Najib when his late father’s efforts improved their lot. Malay culture beholds its people to memories of the good that others have done for them.

In my conversations and interviews with rural Malay communities, a common refrain I hear is to “kenang jasa” or to “remember the good services or efforts (of the past)”.

This is a common belief by traditional Malay communities, but was especially fervent in Johor’s FELDA areas leading up to GE14.

Johor has always been UMNO’s stronghold. While there was a dip in support over GE14, rural parts of Johor remained firmly in UMNO hands.

The expectation is that past “generosity” should be repaid with loyalty at the ballot box, and in recent times, support outside the courts.

UNCERTAINTY POST-GE14

In spite of widespread loyalty to Abdul Razak and UMNO, many voted in protest in 2018. Anger at Najib’s immediate family’s unabashed extravagance was overriding as the population struggled with rising costs of living, the imposed GST and reductions in petrol subsidies.

But few expected the entire Barisan Nasional (BN) government to fall.

The aftermath was total bewilderment, some regret and quite a bit of trepidation at the incoming Pakatan Harapan (PH) government. At that point, Malaysia had not had a change in government since independence and many were concerned about possible sweeping changes to come.

This sentiment was especially directed towards the Democratic Action Party (DAP) – long vilified as the despised ethnic other and nemesis to Malay culture, faith and rights.

Malaysians used to having BN in power grappled with a completely new world. While the GST was removed, the PH government created a sales and services tax, and costs of living continued to rise.

Past collegial methods of doing business were replaced with systems said to improve transparency and remove corruption but were a shock to the people.

It was at this time around 2019 that Najib began to reinvent himself, even as corruption, abuse of power and tax evasion charges were filed against him.

THE RISE OF “BOSSKU”

Stemming from Facebook posts of him riding pillion in a rural village, to asking which motorbike model is better to a subsequent sketch of him sitting astride a motorbike with the licence plate 8055KU, the Bossku narrative took social media by storm.

Intentionally or otherwise, this became his new persona. In public engagements, his supporters and even random foreign workers in the vicinity could be heard calling out to him as Bossku.

From elitist prime minister, Najib was now seen as someone on the ground with the people, accessible to all, and a voice for the everyday Malaysian.

Past anger at his family’s brazen displays of wealth evaporated and “malu apa bossku” (what are you ashamed of my boss?) became the rallying cry of the poor.

The tagline became a catchy rap that spread quickly through B40 communities and even spawned T-shirts, caps and other merchandise. These were bought and worn by people of all ages as a symbol of solidarity and displeasure at the PH government.

Despite many UMNO MPs crossing over to Bersatu, the reality was that PH did not have the grassroots network to effectively engage with the rural poor. They were deemed distant, aloof and irrelevant. These views were fuelled and strengthened by BN social media warriors.

The irony that Najib is now advising the UMNO grassroots not to exhibit luxury and instead work for the people, when he himself was deposed from power for those same reasons, seems to be completely overlooked by his fanbase.

A PANDEMIC KNOCK-OUT PUNCH

Then came COVID-19, and with it, a whole new wave of uncertainty. It brought the country to an unprecedented economic standstill and total lockdown. It fuelled a political crisis culminating in a changeover in government.

As movement restrictions dragged on well into 2021, nostalgia for Najib’s era of relative stability strengthened. Economic disruption hit the people hard. Incidents involving national leaders and celebrities flouting rules added salt to the wound.

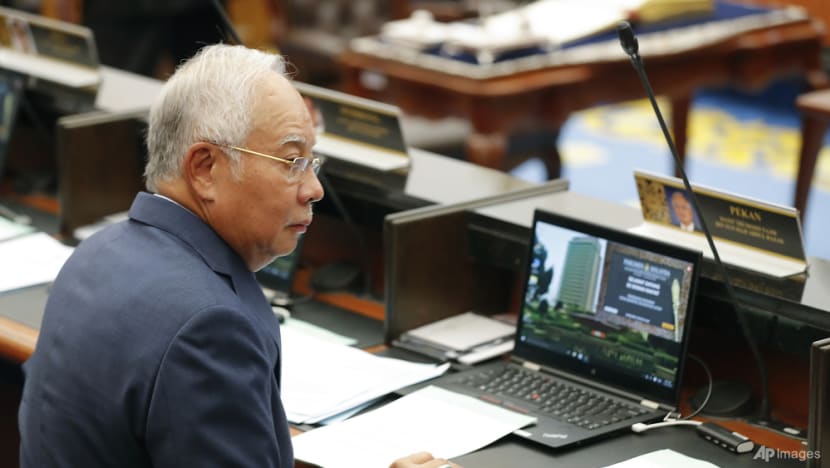

As Najib peppers his social media pages liberally with the local chant of “malu apa bossku”, he is simply parroting public concerns in parliament on behalf of the people.

Some Malaysians think he understands their difficulties and will fight for their rights. Hence the calls for him to return as prime minister.

CAN BOSSKU RETURN AS PM?

But on paper, and by law, Najib’s return as PM is not actually possible. Anyone charged and found guilty of this many severe crimes cannot stand as a representative of the people or as a member of parliament.

But there is still the ongoing appeal at the Federal Court, and the never-ending stay of execution.

In spite of the charges against him and the fact he’s been found guilty, Najib has been walking around a free man.

While Najib is seen to be the invisible hand behind UMNO’s win in the recent Melaka state elections, and a vital power-broker within the party given his broad support base and deep pockets, there are factions against him.

Some are envious of his position and power and would like to replace him. Others are publicly outspoken against his role in the 1MDB saga.

UMNO party divisions and branches are now visibly mobilising in preparation for early national elections in 2022. Many analysts see this as a bid by Najib to build on the Melaka elections and regain full power.

It is broadly assumed that if he can be reinstated as prime minister, he can be cleared of all charges. His appeal at the Federal Court will take many months to come to a conclusion in any case.

Najib could also ask for a royal pardon, which can be granted on the advice of the Royal Pardons board – the same body that recommended Anwar Ibrahim’s 2018 pardon. However, this option is often exercised as the very last available alternative in a politician’s portfolio.

This all seems impossible, but several high-profile corruption and money-laundering cases involving UMNO secretary-general Ahmad Maslan, former Sabah chief minister Musa Aman and Riza Aziz (Najib’s stepson) have recently been acquitted, discharged on technicalities or after having paid fines.

By Serina Rahman / CNA