EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

- The Twelfth Malaysia Plan (12MP) clearly and vigorously advocates the “Bumiputera agenda”, while outlining policies designated for minority groups and women, saliently in higher education, entrepreneurship and decision-making positions.

- The demarcation of the Bumiputera agenda, which is based on programmes under Bumiputera-mandated agencies instead of more systematic criteria, only partially accounts for the vast Bumiputera preferential system.

- The 12MP recognises that the major shortcomings in Bumiputera development pertain to higher education, skilled occupations and entrepreneurship, but fixates on equity ownership, especially in Prime Minister Ismail Sabri’s 27 September speech to Parliament. The 12MP also omits problems of inequality within the Bumiputera population, and questions surrounding majority and minority interests, especially in higher education.

- Malaysia missed an opportunity to reset the agenda by focusing resolutely on developing Bumiputera capability and competitiveness, and formulating group-targeted policies in an integrated manner that accounts for majority and minority interests.

- Provisions for minority groups and women need to go beyond tokenism, and development policy on the whole must systematically balance need, merit and identity – giving preference to the disadvantaged, promoting achievement and fostering diversity.

INTRODUCTION

The Twelfth Malaysia Plan, 2021-25 (12MP) for a “Prosperous, Inclusive and Sustainable Malaysia” was unveiled by Prime Minister Ismail Sabri on 27 September 2021, and speedily approved by both the Dewan Rakyat (7 October) and Dewan Negara (21 October).[1] As expected, Bumiputera preferential programmes feature prominently. The 12MP retains the term “Bumiputera Economic Community”, first articulated in the Eleventh Malaysia Plan (11MP) to encapsulate the policy beneficiaries, but forthrightly advocates for pursuit of the rather semantically loaded “Bumiputera agenda” (Malaysia 2015, Malaysia 2021).[2]

The 12MP’s signals of policy continuity and deployment of more assertive language presage some expansion and intensification of pro-Bumiputera programmes, but not necessarily in a drastic manner. The Plan’s launch coincides with UMNO’s return to power, but Bumiputera policies are fundamentally constant and embedded, as demonstrated by the numerous Bumiputera development promises made in Buku Harapan, Pakatan Harapan’s 2018 election manifesto, and by the fact that the 12MP’s formulation began in 2019 while Pakatan Harapan held federal power.[3] This signature national policy remained intact through two changes in government.[4] A deeper and more critical reading of the 12MP will notice the collation of Bumiputera policies and other group-targeted policies – for the Orang Asli, Indians, new village Chinese, women and persons with disabilities – into one distinct segment of the report. In this regard, the 12MP has retained a template laid in the 11MP, which helps clarify the government’s stance of supporting non-Bumiputera, especially Orang Asli, development.

Public discourses overwhelmingly focus on Bumiputera quotas and privileges, while policy debates are perennially reduced to the question of continuing versus terminating Bumiputera policies. However, interventions that benefit other ethnic groups and women belong to the same policy domain of group-targeted policies. Malaysia needs to take a systematic and cohesive approach, and to make a distinct break from the polarised deadlock.

This Perspective critically engages with the 12MP’s group-targeted, identity-based policies. The mapping of the Bumiputera agenda and outreach to other groups, while improved in recent years, still suffers important omissions (Lee 2019a). A more complete and valid delineation must go beyond the tokenism for minorities that continually characterises public policy, and account for intra-Bumiputera disparities and areas of majority-minority contestation. The persistent primacy given to the 30% Bumiputera equity ownership target detracts from a focus on skills, capability and competitiveness that the 12MP itself acknowledges as decisive policy shortcomings. On the whole, the 12MP constitutes a foregone opportunity to resolutely develop capability and to formulate group-targeted policies in a systematic, productive and inclusive manner.

MAPPING THE BUMIPUTERA AGENDA AND GROUP-TARGETED POLICIES

The Bumiputera agenda and corresponding policies for other target groups operate in specific areas of socioeconomic empowerment, with the objective of fostering equitable representation and promoting achievement in higher education, skilled occupations, decision-making positions, enterprise and ownership. Locating and quantifying the 12MP’s outreach to distinct groups constitutes the first step in scrutinising this policy domain.

Chapter 5 of the 12MP, entitled “Addressing Poverty and Building an Inclusive Society”, includes a six-page Priority Area section on “Achieving an Equitable Outcome for Bumiputera” that sets out, with considerable detail, the measures to roll out in the next four years for the community. Other Priority Areas include a two-page “Enhancing Development of Orang Asli Community” and three pages of “Empowering Specific Target Groups”, of which half a page pertains to empowerment policies for women and persons with disabilities (with most of the section concerned with welfare and basic provisions for children and the elderly). Within Priority Area “Empowering the B40” (bottom 40% of households) we find two paragraphs sketching out assistance for low-income Indian households and Chinese new village residents.

The disproportionality in space allocation is striking, albeit not surprising; Bumiputera-targeted empowerment programmes have predominated in Malaysia’s policy regime since 1971 under the New Economic Policy (NEP). The NEP was launched as a component of the Second Malaysia Plan (1971-75), and all successive five-year plans have incorporated it. However, two further issues arise in the context of the 12MP.

First, the document demarcates the Bumiputera agenda according to government agencies that oversee certain Bumiputera programmes – Teraju, MARA, PUNB, Ekuinas, PNB, YPPB[5] – instead of a systematic and comprehensive catalogue of all policies and entities promoting Bumiputera development through preferential, group-targeted interventions. The 12MP’s mapping omits a host of programmes that massively provide opportunity for Bumiputera socioeconomic advancement – most saliently, matriculation colleges and pre-university programmes, higher education and skills training, including Universiti Teknologi MARA (UiTM), public sector and GLC employment, and public procurement (Lee 2017).

The Plan emphasises the importance of cultivating talent and building SME capacity, but neglects to channel such resolve and vigour toward these programmes that lie beyond the purview of Bumiputera-mandated agencies. For instance, public procurement plays a major role in Bumiputera enterprise development; its underperformance curtails potential gains to Bumiputera contractors. The 12MP extends existing schemes in public procurement, but refrains from bold measures.

Second, the restricted recognition of the Bumiputera agenda also precludes important attention to: (1) disparities within the Bumiputera population, particularly between Sabah-Sarawak versus Peninsular Malaysia, and; (2) majority-minority contestations, which are particularly pronounced in the fields of higher education enrolment and scholarships.

The 12MP provides neither a review nor outlook of equitable distribution between Bumiputera populations of Sabah-Sarawak and the Peninsula. Again, there is a story of continuity; Malaysia’s official statistical publications have since around 2013 ceased differentiating Malay and non-Malay Bumiputera, or any other disaggregation of the Bumiputera category that now accounts for 70% of Malaysia’s citizenry. Still, this void of concern for equity between East and West Malaysia stands out, considering the 12MP’s unprecedented inclusion of a full chapter on Sabah and Sarawak. Chapter 7 on “Enhancing Socioeconomic Development in Sabah and Sarawak” addresses regional economic development, with cursory coverage of measures targeting Anak Negeri Sabah and Bumiputera Sarawak, the states’ indigenous peoples who officially qualify for Bumiputerabenefits.

Regional disparities are policy concerns that the 12MP continues to track, in terms of differentials in income and poverty between states. However, there is no monitoring, or target-setting, on the widely acknowledged lagging development of indigenous groups, and no explicit commitment to narrowing gaps between Malays on the Peninsula relative to Bumiputera counterparts in East Malaysia. Among the most recent data showing the disparity is the 2013 Labour Force Survey Report, which showed that 31% of Malay labour had attained tertiary education (certificate, diploma or degree qualifications), far above the 18% recorded for non-Malay Bumiputeras (DOSM 2014).[6]

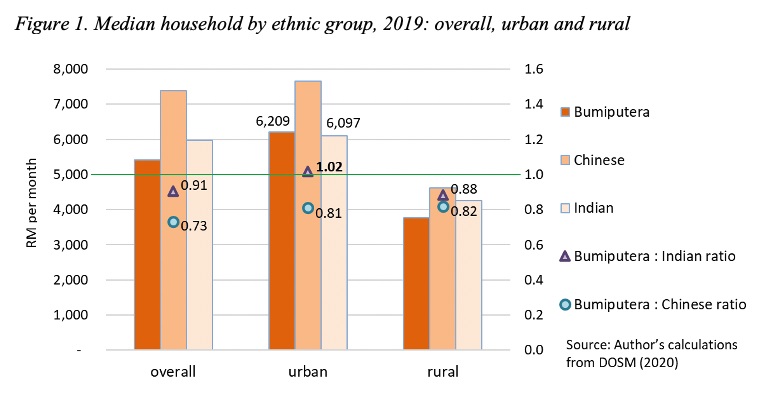

Policy mapping that is supposed to lay the foundations for group-targeted policies ought to be grounded in empirical evidence of inequalities between groups. Indeed, the Malaysia Plans for decades continually provided updates on income disparities between Bumiputera, Chinese and Indian households. The 12MP only compares Bumiputera to Chinese household income while altogether dropping comparisons with Indian households, and only reports the combined national average without distinguishing urban and rural populations. The Chinese and Indian populations are overwhelmingly urbanised; Bumiputeras account for the vast majority of the rural populations, where incomes and cost of living are lower. 74% of the Bumiputera working age population (15-64 years) are urban, compared to 95% of corresponding Chinese and Indian. Bumiputeras account for 91% of the rural working age population, much higher than their 62% share of the urban working population (author’s calculations from DOSM 2021).

Hence, the more credible inter-ethnic comparisons should separately compute urban and rural inequality statistics, with a focus on the urban. The 12MP reports the national Bumiputera-to-Chinese median income ratio of 0.73; at the median, Bumiputera households earn 73% of Chinese households (Figure 1). The gap narrows to 0.81 when we focus on urban populations. Importantly, the Bumiputera households are basically on par with Indian households, registering a ratio of 1.02. As shown in the middle set of bars in Figure 1, half of urban Bumiputera households earned less than RM6,209; while half of urban Indian households earned less than RM6,097. Much less assistance is designated for the urban Indian population despite their similar socioeconomic status to urban Bumiputeras.

The 12MP’s tokenism for minority groups also shows up in the narrow identification of B40 Chinese new villagers as a target group, and the absence of provisions for the community in general. The specific designation of Chinese new villages as policy beneficiaries may be valid on socioeconomic grounds, but also reflects inertia, considering new villagers have been a political constituency repeatedly featuring in Malaysia Plans.[7] However, retaining this practice stands out further amid the 12MP’s reassertion of the Bumiputera agenda – as well as the absence of the Indian community in the empirical mapping of socioeconomic disparities. Access to public higher education, a perennial complaint of minorities who experience or perceive unequal opportunity – as a consequence of Bumiputera preference – has also long been excluded in the Malaysia Plans, but its relevance may swell if private higher education becomes less available or less affordable as an alternative, in the aftermath of Covid-19.

MISALIGNED DIAGNOSES AND PRIORITIES

Development planning stems from diagnoses of development problems, which in turn determine priorities and goals. The 12MP quite perceptively evaluates the shortcomings of Bumiputera development. Foremost on a list of conditions that hamper the community’s breakthrough in economic empowerment are concentration of MSMEs at the micro scale and participation in low value-added activities, along with reliance on government assistance. Likewise, the 12MP maintains that human capital and entrepreneurship take precedence as policy objectives (Malaysia 2021, 5-30 and 5-31, italics added):

- “Human capital development will be the main focus in uplifting Bumiputera socioeconomic position”

- “Increasing the resilience and sustainability of Bumiputera businesses will be the main focus in strengthening entrepreneurship culture.”

These diagnostics and priority-setting should guide the Bumiputera agenda to place emphasis on higher education, SME development and capacity building as principal goals.

Nevertheless, the driving objective of the 12MP, emphatically expressed in the Prime Minister’s 27 September parliament speech, is 30% Bumiputera equity ownership. Of the vast range of Bumiputera socioeconomic conditions and unfinished business that could have been highlighted, the shortfall in equity ownership received pride of place (Ismail Sabri 2021). The equity target plays a symbolic role and has continuously been drummed up as a communal rallying cry for political gain, but the policy ramifications are substantial (Lee 2021a). The effective relegation of human capital development in the hierarchy is reflected in distinctly secondary targets for 2025: 65% of Bumiputeras in skilled jobs in 2025; and Bumiputera enterprise contributing to 15% of GDP. Despite reporting that a staggeringly high 83% of Bumiputera MSMEs are classified as micro, the 12MP refrains from setting targets for growing the share of small and especially medium enterprises. Such aspirations, while not immune to the pitfalls of patronage and rent-seeking, would be more inclined to be broad-based and productive.

MISSED OPPORTUNITIES

The Bumiputera policy continuously provokes visceral protest; predictably, the 12MP has been decried for maintaining ‘race-based’ policies.[8] These critiques fail to explain how a policy system as embedded and extensive as Malaysia’s Bumiputera regime can be terminated by top-down dictate. The popular discourses typically highlight the politically connected elites who have vested interests in perpetuating Bumiputera policies. However, the vast swathes of Bumiputera society that obtain access and socioeconomic opportunity through the system cannot be ignored. Public opinion surveys emphatically show overwhelming Malay support for the policy.[9] These realities on the ground sustain the policy, and policy reforms have to account for the interests, and possible anxieties, of ordinary Malays. Calls for abolition of ‘race-based’, pro-Bumiputera affirmative action also commit self-contradiction or double standards when they denounce pro-Bumiputera programmes while not opposing or even welcoming special interventions that reach out to the Orang Asli, Indians, East Malaysian indigenous groups, or women, and other designated groups.

Recent Malaysia Plans have brought more clarity on the scope and role of group-targeted policies. The 12MP’s missed opportunities stem from a failure to deal comprehensively and constructively with these policies that have increasingly become mainstreamed. Malaysia has undergone developments paralleled in many advancing economies and maturing societies, where improved material conditions induce a greater valuation and expectation of equitable representation of gender, ethnicity, religion, language and culture in higher education, decision-making positions, business, and upper socioeconomic echelons in general. The pressing question for Malaysia is how to execute group-targeted policies with purpose, fairness and efficacy.

Malaysia’s development planning loosely clustered the Bumiputera agenda together with other group-targeted policies, implicitly acknowledging that they belong together. However, the 12MP refrained from explicitly acknowledging that these special measures are part of the same policy domain, whether designated for Malays, Sabah and Sarawak indigenous groups (officially conferred Bumiputera status), Orang Asli, Indians, other minorities, women, or persons with disabilities. Policies in this domain serve a common purpose of promoting participation, achievement and diversity, and inherently operate by conferring preferences and special treatment, in order to overcome barriers to entry that impede progress or retard the pace of change.

Malaysia’s fragmentary approach forestalls direct engagement on three vital matters. First, Bumiputera development should be focused resolutely and momentously on enhancing capability and competitiveness, while also beginning to devise ways of graduating or exiting from a reliance on overt quotas and preferences. As noted above, the 12MP has clearly identified the lack of skilled employment and entrepreneurship as major shortfalls; policies should thus be galvanised around these priorities. The 12MP also mildly hinted at the introduction of “exit plans” to mitigate protracted dependency, and measures to “encourage” the Bumiputera T20 (richest 20%) to “actively contribute back to the Bumiputera community”. However, no details were supplied. The T20 deserve the spotlight and assigned lead roles in graduating out of preferential treatment, being the strata that has gained the most upward mobility – undoubtedly through effort, but typically also as beneficiaries of scholarships, upward occupational mobility, contracts, or loans. In short, the T20 should be the first in line to publicly demonstrate some relinquishment of privileged access.

Second, Malaysia’s group-targeted policies need to be comprehensively and systematically formulated, integrating the broad range of interventions, balancing majority and minority interests and fostering equitable distribution. The notion of replacing ‘race-based’ policies is often articulated without elaboration on what this move entails and whether ‘race-based’ policies for minority groups will also be eliminated. The antagonistic tone of such stances also forestalls conversations. Another transition Malaysia can take – arguably, a more productive and cohesive one – begins with a recognition of the positive and enduring roles of identity-based, group-targeted policies. This also involves fostering equitable opportunity in higher education, especially public universities, which persists as the area of heightened majority-minority contentions.

There are no simple solutions in this policy sphere, but there is considerable scope to branch away from ethnic quotas and devise integrated selection modes that take into account disadvantaged background, academic achievement and student diversity in allocating higher education opportunity. As with the Bumiputera agenda, the focus on all programmes for all target groups must focus on promoting capability. Across the board, relatively disadvantaged groups – Orang Asli, and poor segments of the Indian and East Malaysian indigenous populations – will be better served by expanding their access to skills acquisition, higher education, self-employment, and SME development.

Third, the 12MP, in relaying the mantle of inclusive development, needs to practically and visibly open up hitherto Bumiputera-only programmes to other groups. Such demonstrations stand to benefit all sides, by signalling to the majority that they can continue to enjoy socioeconomic opportunity even while letting go of exclusive access, and assuring the minorities that the country is genuinely delivering on the goal of inclusiveness. The prospects are daunting, especially considering the general track record of the Bumiputera system’s intractability toward change, and fervent resistance to inclusion of non-Bumiputeras in specific institutions such as UiTM.

However, more thoughtful and tactful solutions have scarcely been broached. Recently established, and less baggage-laden, state-supported institutions present more hopeful starting points, particularly if they benefit lower-income households and hence fulfil the moral principle of prioritising the less privileged. YPPB (Yayasan Peneraju Pendidikan Bumiputera) provides scholarships and practical support for disadvantaged Bumiputeras in technical and professional programmes; it was started only in 2012 with the express mission of reaching out to students from challenging and difficult family backgrounds – an abiding principle that underscores the aptness of outreach to non-Bumiputeras, especially Indian and Orang Asli youth, who are encumbered by family circumstances. Likewise, microfinance, SME loans, and advisory services offered by Tekun and PUNB (Perbadanan Usahawan Nasional Bumiputera), operate primarily for the benefit of lower income Bumiputera households. Tekun runs one scheme for Indian entrepreneurs, and in recent budget allocations it has received disproportionately less federal funding. Hence, there is much room for growth.[10] PUNB, being under the jurisdiction of the investment giant PNB (Permodalan Nasional Berhad), also holds out potential to follow the notable precedent of its parent, which started out offering unit trust savings exclusively for Bumiputeras but later became accessible to more Malaysians.

CONCLUSION

The Twelfth Malaysia Plan inherited a template of policies promoting upward mobility and participation of the Bumiputeras and other targeted groups; this point injects some clarity but also exposes some of its limits and omissions. It is timely and pertinent for Malaysia to focus on this domain of group-targeted interventions in a comprehensive and integrated manner. A new and more impactful approach is needed, encompassing all ethnicities and other identity categories such as gender and disability, and going beyond the 12MP’s delineation of “the Bumiputera agenda” as the activities of Bumiputera-mandated agencies, which omits many large and important pro-Bumiputera interventions. Contestations between majority and minority groups and disparities within the Bumiputera population, largely ignored in the 12MP, also demand more robust attention. The provision of Covid-19 relief through some Bumiputera-exclusive institutions – specifically, microfinance institutions Tekun and PUNB – reinforces the need for more ethnic inclusiveness in such programmes, in which low-income status should weigh much more than ethnic identity.

While credibly assessing that the major shortcomings in the Bumiputera development pertain to skills and entrepreneurial capacity, the 12MP inadequately follows through; it retains fixations with equity ownership instead of decidedly prioritising capability development and broad empowerment.

Malaysia’s next national master plan fails to reformulate policy in three key aspects:

- Mapping group-targeted policies comprehensively and clarifying the role of identity-based policies – especially based on ethnicity and gender – in the development process;

- Setting capability and competitiveness as the driving objectives, especially for the vast Bumiputera programmes, and devising graduation or exit plans;

- Fostering equitable access and balancing majority-vs-minority group interests to truly deliver on the mission of inclusiveness.

by Lee Hwok Aun / iseas

The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of AsiaWE Review.