In the end, the United Kingdom got what it wanted: come hell or high water, an in-person Conference of Parties (COP) in Glasgow. It was an extraordinary event that saw 120 heads of state and governments in attendance, a record number since the signing of the Paris Agreement in 2015. Chinese president Xi Jinping and Russian premier Vladimir Putin chose to skip the meeting. But several significant high-level political pledges were delivered: the US-China Joint Glasgow Declaration on Enhancing Climate Action in the 2020s, India’s declaration to achieve net-zero in emissions by 2070, the Glasgow Leaders’ Declaration on Forests and Land Use, and the Global Methane Pledge jointly led by the US and EU.

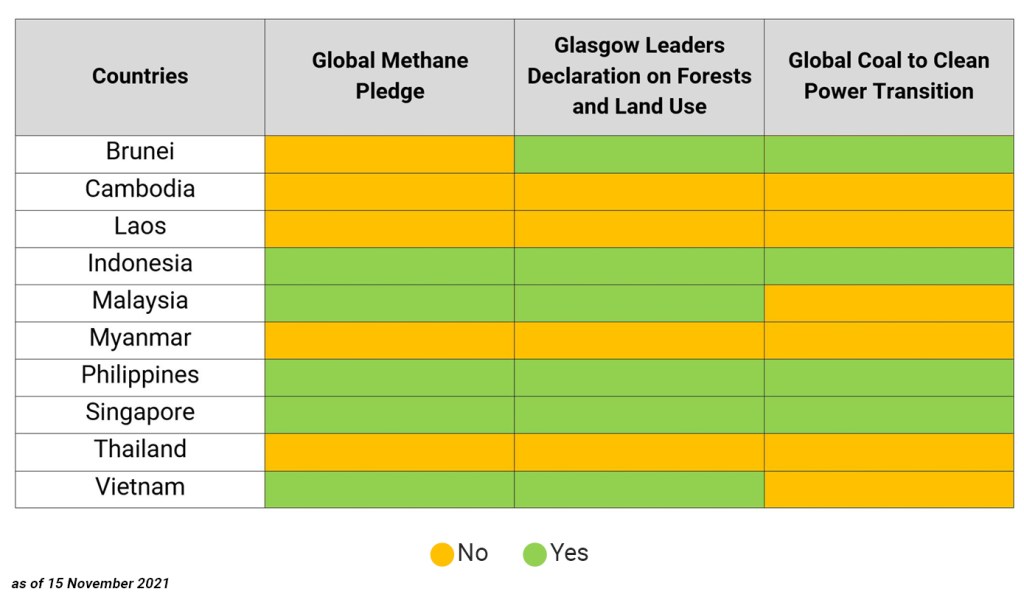

The table below shows Southeast Asian countries’ commitments to some pledges. A word of caution: high-level pledges does not necessarily mean follow through and implementation.

Here are six key takeaways of COP26 for the region:

- Indonesia’s Critical Role

Indonesia’ commitment to the phase-down of fossil fuel subsidies and the global goal to end deforestation by 2030 will contribute to significant regional emissions reduction. Indonesia is both the region’s top emitter and also its biggest carbon sink.

But Indonesia’s plans to phase out coal-fired power plants by the 2040s comes with so many caveats that environmentalists accuse the Jokowi government of extending a lifeline to the coal industry. Prior to COP26, President Jokowi frequently stated that Indonesia has played a part in advancing climate goals, citing Indonesia’s successful efforts to conserve forests through the country’s moratorium on new lodging and plantations permits. The new deforestation agreement places greater responsibility on countries with carbon sinks and allows for fairer compensation with a US$20 billion package for forest protection and restoration. There are also concerns that phasing out coal and ending deforestation could hurt the Indonesian economy.

- The Broken Promise of Climate Finance

The commitment by developed countries in mobilising US$100 billion annually in climate finance by 2020 to support mitigation and adaptation has fallen short. OECD figures show that climate finance only reached US$79.6 billion in 2019 with no clarity whether the commitment is funded through public finance or private finance. Oxfam data further suggests that the actual level of climate-specific grants is only one-fifth of the top-line figure if loans are taken out.

The broken promise of climate finance disadvantages many Southeast Asian countries with many emphasising the need for international assistance in the Nationally Determined Contribution (NDCs). Indonesia, the Philippines, and Cambodia, in particular, are committed to ambitious carbon emission reduction conditioned on receiving international assistance.

- Phasing Down Instead of Phasing Out Coal Power

UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres’ call to ‘consign coal to history’ went unheeded. A global pledge to end the use of coal was not supported by the US or China. President Joe Biden was criticised for his Glasgow performance. He had refused to join the pact while signing off on numerous oil permits back home.

A last-minute deal between China and India led to the watering down of ‘phase out’ to ‘phase down’ of coal power. It is historic and a step forward that the word ‘coal’ has been mentioned in the text, but it strains credulity to think that the fossil fuel most responsible for global warming was never mentioned in the preceding 25 texts. The compromise has been labelled a cop-out to coal-intensive countries, so they can continue to emit behind the rhetorical cover provided by words such as ‘unabated’ and ‘inefficient’.

China’s attitude at the conference was equally disappointing. Earlier this year, President Xi Jinping provided a glimmer of hope when he stated that China would no longer provide financing for overseas coal plants, including in ASEAN. Now that China has pledged only to phase down coal consumption domestically, its climate leadership has taken a hit.

- New Commitment to Reduce Methane Emissions

Discussion over methane emissions has been rather peripheral until now. Cutting methane, a greenhouse gas with high global warming potential, offers a faster way to slow down global warming.

More than 100 countries, including Singapore, Indonesia, Vietnam and the Philippines from ASEAN have committed to cutting methane emissions by at least 30 per cent by 2030. However, China, Russia and India, which together contribute 35 per cent of global methane emissions — have not signed the pledge. The trio needs to get into the game.

- US-China Common Ground

That the two largest carbon emitters and long-time adversaries finally have reached common ground to strengthen the implementation of the Paris Agreement was greeted with much cheer.

This is a positive outcome for Southeast Asia, the region where the two major powers compete for strategic influence. The hope is that China and the United States can work together to fill much-needed climate investment gaps in Southeast Asia. China could focus on providing green investment and embedding climate risk calculations in its Belt and Road Initiative. Whereas the United States, through its new Build Back Better World initiative, can provide capacity building and technical know-how, and bring businesses and industries that can play a part in the region’s low carbon transition.

- Finalisation of Paris Rulebook

The good news from COP26 is the finalisation of the Paris rulebook after six years of wrangling over transparency, common time frames and Article 6. The latter disagreements were over whether to allow the carry-over of carbon credits from the Kyoto Protocol era, whether the share of proceeds should go to an Adaptation Fund and ensuring that the credits are of high quality. The finalised rulebook will help countries to operationalise provisions with greater clarity and transparency.

Grace Fu, Singapore’s Environment Minister, who co-chaired the negotiations with Norway on the contentious Article 6, has hailed it as a win for multilateralism. With several ASEAN countries already or planning to engage in voluntary carbon markets, Article 6 promises strong incentives for countries like Indonesia and Vietnam to protect their forests and achieve mitigation targets.

The post-COP26 homework for countries will be to integrate their new pledges into the enhanced NDCs for 2030 and implement them fully. According to United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), the world is on track for a global temperature rise of 2.7 degrees, even after accounting for the updated NDCs. In an addendum to its Emissions Gap 2021 Report, the UNEP cautioned that since these global announcements do not form part of national pledges, the dial is not expected to shift much. If implemented effectively, warming can be limited to 2.2 degrees, which is still some ways off the 2-degrees goal, not to mention 1.5 degrees.

Alok Sharma, COP26 President, said that the 1.5 degree goal has been kept alive, but ‘its pulse is weak’. Putting 1.5 degrees on life support will require every country to implement commitments with immediate effect. As host of COP27, Egypt will have the thankless task of pushing the envelope.

By SHARON SEAH, MELINDA MARTINUS and RYAN WONG / fulcrum

The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of AsiaWE Review.